On March 16, 2018, I delivered the opening keynote for Appdevcon, which was titled Building Better Software by Building Better Teams. Slides are here. This post serves as a kind of pseudo-transcript of the talk. I also did an interview with the conference organizers after my talk.

Hello! I’m Ash Furrow, and I’ve been writing iOS apps since 2009. I’ve also helped build business-critical systems in Swift, Objective-C, Node, Scala, Rails, React – all kinds of stuff. And today we’re going to talk about how we can build better software by building better teams.

Two and a half years ago I wrote this blog post about building online communities. It was inspired by seeing a talk by Justin Searls called The Social Coding Contract about online communities. That month I wrote another post about how the next step in my career was going to become a community-builder: someone who builds teams. I ran that idea by my manager at Artsy, and then by our CTO, and I had their full support.

I began researching team dynamics, community structures, and online empathy. Part of my job became to learn about team building and apply it to Artsy. I’m not an expert in this field, but I’ve focused the past two and a half years on learning how to build teams, online and in-person, both in open source and business contexts.

When I started, I wrote the following:

… believing in something isn’t enough to make it happen. It takes planning and consistent action.

I’m still learning, and I’m still working on these skills. And today, I’m really excited to share some of what I’ve learned with all of you. So let’s get started!

My goal today is to convince you that team building improves software quality, and to provide you with a vocabulary to discuss team quality.

Team Quality Affects Software Quality

Before we discuss how to use the quality of a team to influence the quality of the software produced, we need to define the relationship between team quality and software quality.

So let’s step back and think at a slightly higher level. Developers often think that software teams are unique or special among teams, but that’s not true from an organizational perspective. We tend to think that building software is unique among other types of work, that we have unique needs and distinct characteristics that mean that organizational behaviour principles don’t apply to us. But every type of worker is unique and every field has their own distinct way of working. We can acknowledge what makes building software unique while still looking to other fields for lessons in structuring teams.

Let’s borrow observations of other types of teams and apply them to teams of software developers.

Amy Edmondson is a professor of Leadership at Harvard Business School. She was studying medical teams in hospital settings in the 90’s, and wanted to establish a correlation between patient outcomes (post-operation complications, things that can be easily and objectively measured) with team quality. She initially hypothesized that teams that reported making the fewest mistakes would be the ones with the best patient outcomes, but was surprised to find the exact opposite: teams with better patient outcomes reported making more mistakes.

Investigating further, she discovered that teams with poorer outcomes were reluctant to admit mistakes because they feared being humiliated or shamed by their peers. So mistakes were hidden. This prevented the team from learning from the mistake and preventing the same mistake from happening again.

In contrast, effective teams (with better patient outcomes) readily discussed their mistakes. That way, everyone was able to learn from them. They felt safe to ask questions and suggest ideas, too, without fear of being ridiculed. The team’s outcomes benefited greatly from the individuals’ freedom from fear of humiliation.

Her research led Professor Edmondson to a concept she named “psychological safety.” We’ll get into what that means later.

My point is that the relationships between team members (the quality of a medical team) had a direct and measurable impact on the quality of the team’s output (patient health). The medical staff who were comfortable admitting and reporting mistakes knew that they would not be ridiculed or judged for them, and so the whole team benefited from the learning opportunities of those mistakes.

We can generalize a bit: just as the quality of the medical team affected the quality of patient outcomes, team quality generally affects team outcomes. Since software teams are teams like any other, the quality of the software team is going to affect the quality software they produce.

- A junior developer thinks they see problem in the network layer of an app. It was written by a senior member of the team. Will they feel comfortable pointing it out to their team?

- A programmer at your startup is rushed by a deadline. They are exhausted and have started making mistakes. Will they feel comfortable getting the rest they need in order to keep your app from crashing during an investor pitch?

- A designer sees a complex animation that’s been implemented incorrectly, breaking the visual metaphor of the whole app. There’s not enough time to re-implement it from scratch, will the designer approach the app developer and work together on a compromise for v1?

(Note: I didn’t say so during my talk, but the developer in each of these examples was… me!)

The prime directive of this post is: everyone on your team assumes that everyone else on the team is doing their best work, given their circumstances. When you start from that shared understanding – that you’re all doing your best you can – you can foster a compassionate working environment.

Compassion Facilitates Teamwork

Suffering is a normal and inevitable part of life. Since work is a part of life, suffering will be a part of work, too.

But just because suffering is inevitable doesn’t mean that all suffering is inevitable. It can be avoided, and it can be minimized. Compassion is defined as the process of minimizing suffering. And in that sense, “compassion” is an optimization problem: to minimize suffering.

Being compassionate in our teams is about minimizing the suffering of our teammates (and ourselves!).

Optimizing something – anything – is something developers specialize in. We optimize app launch times, memory footprints, scrolling performance, so we should approach compassionate work on those terms.

So how does one minimize suffering? Well there are two main ways:

- Respond to suffering with respectful inquiry.

- Anticipate suffering and avoid/minimize it.

This can be really hard because it requires empathy, which is a skill that developers are not known for. But that’s only because we don’t practice those skills! Every programmer and every human being is capable of empathy; it is only a matter of practicing the skill until it becomes a habit.

Theresa Wiseman, a nursing academic, conducted a literature review of the study of empathy and concluded that empathy consists of four necessary components:

- Sharing another person’s perspective.

- Sharing another person’s feelings.

- Staying non-judgemental about those thoughts and feelings.

- Communicating that you understand (in a non-judgemental way).

That last one gets missed a lot. It is not enough to understand what a person is thinking, to understand what they’re feeling, and to stay non-judgemental. Empathy involves communicating your understanding back to the other person.

These individually are skills that you can practice. They are skills that I am still practicing, too.

Responding to suffering with empathy is done through “inquiry work”, and is difficult to get right. But, like empathy, it is a skill that you can develop. When inquiring about a colleague’s suffering, stay respectful. Frame your inquiry around genuine concern and the prime directive. Remember: everyone assumes that everyone else is doing their best.

- If a team member’s number of commits have dropped, will you inquire about potential suffering or leave them alone to face disciplinary action later on?

- If one team member harshly reviews another team member’s code in a pull request, will you inquire about why they were harsh or leave them alone, lowering the bar for tolerable behaviour on your team?

- If an open source developer expresses remorse about not fixing an bug sooner, will you inquire about why they feel bad (and remind them that open source developers are volunteers) or leave them alone to feel needlessly bad?

This can all be difficult, and it is definitely easier to ignore these situations. In fact, it is tempting to not inquire about suffering out of some misplaced sense of empathy. But if someone’s work performance has dropped, is it really better to ignore their suffering until the point that disciplinary action is required?

Anticipating suffering also involves empathy, but in a different way. We can’t inquire about how they’re feeling about an event that hasn’t occurred yet, so we have to use our intuition and empathy to construct and idea of what they could feel and think.

Once you understand someone’s thoughts and feelings without judging them, you can begin to anticipate how events will affect them. Even if you don’t know a person well, focus on the similarities you have with them to foster empathy. Are they working in a similar field? Are they at a similar career stage as you? Are they working in the same company? These similarities help you empathize.

- The end of a sprint is approaching. Will you investigate your teammates’ wellbeing or leave them alone until after the sprint has failed to find out that they needed help?

- If your team is switching from Swift to React Native, will you talk about a teammate’s possible apprehension around being left behind or leave them alone so they feel isolated?

- If there is going to be a change in team reporting structure, will you inquire about a colleague’s apprehension about a prospective change or leave them alone to find out via email and let their imaginations run wild?

Compassion is an optimization problem: to minimize suffering. And we can do that through inquiry work when we notice suffering, and through anticipating suffering to avoid it.

Moving on from minimizing suffering, we come to another powerful tool of effective teams: feedback.

Feedback is a gift.

My colleague says that “feedback is a gift.” When he first told me that, it changed how I thought about feedback. I realized I didn’t feel grateful for the constructive feedback I was getting, and I wasn’t giving adequately constructive feedback either. If I didn’t have something positive to say about a colleague’s work, I didn’t say anything.

I still struggle with this. But I try to make sure the feedback I give is a gift worth receiving, and to listen to feedback I’m given as the gift that it is.

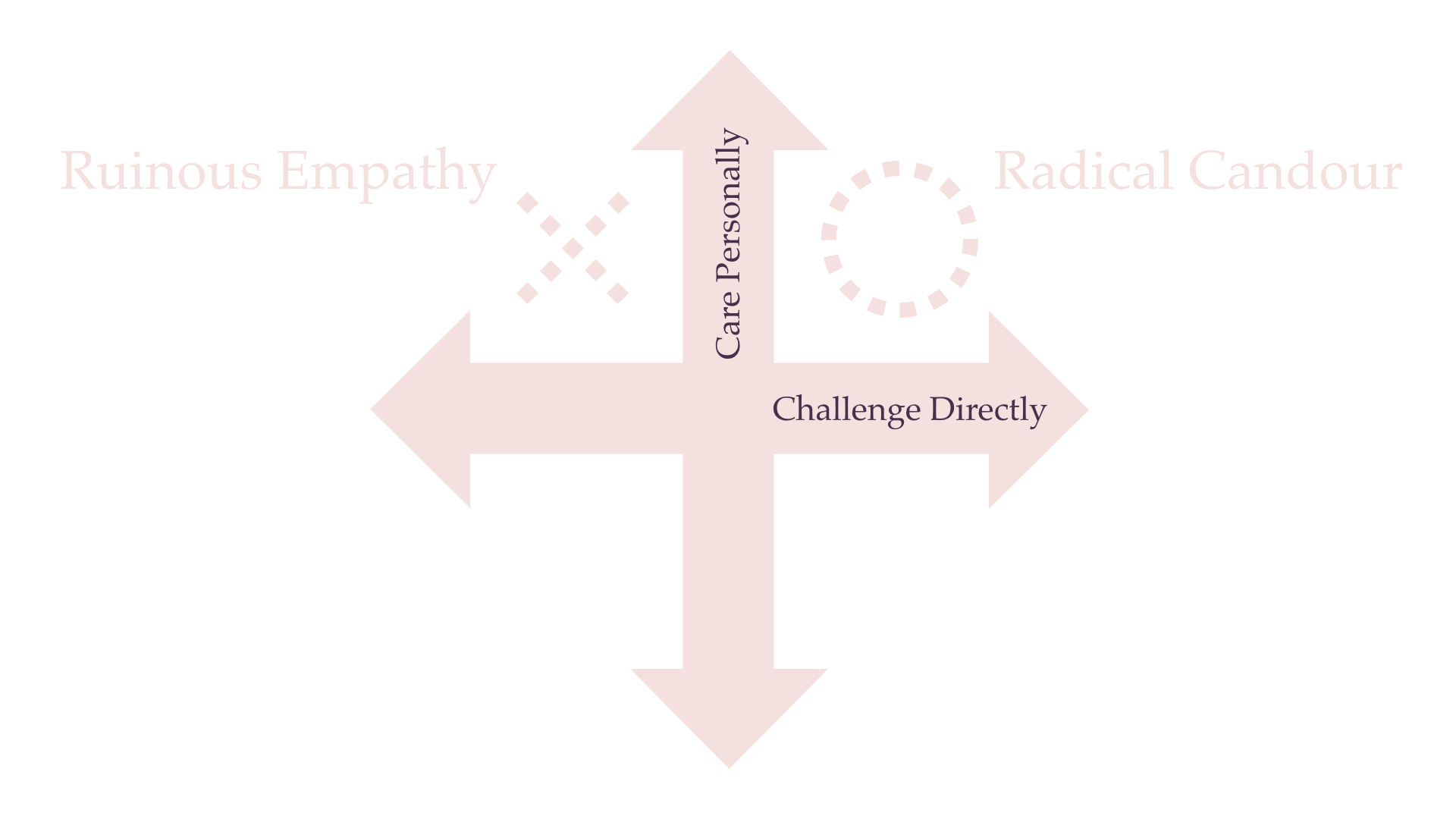

A useful framework for thinking about how to approach our colleagues when something is wrong is called Radical Candour, which is the name of a book on the giving and receiving feedback.

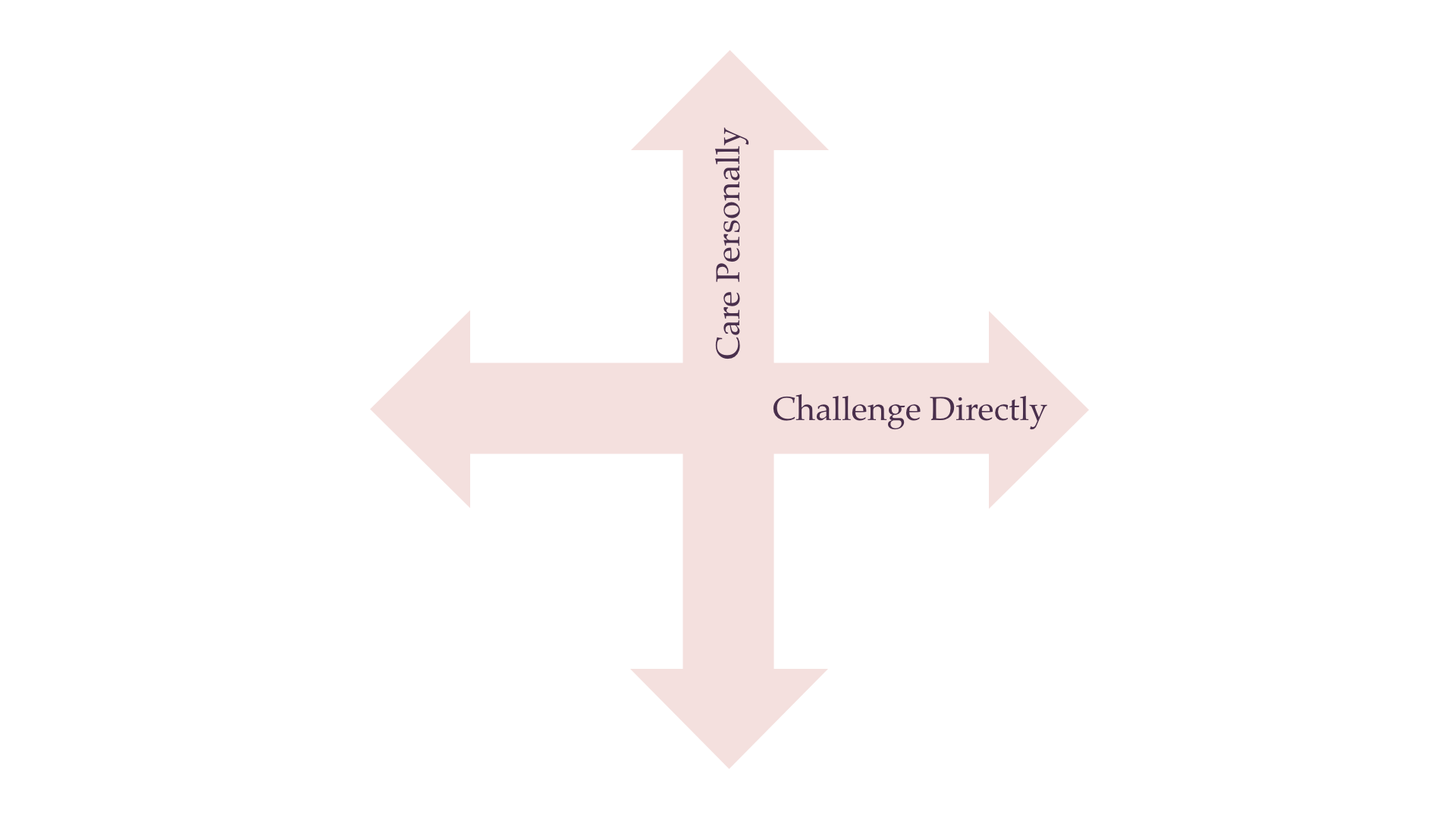

Imagine a graph with the vertical axis representing whether or not you care personally about a colleague, and the horizontal axis representing whether or not you’re willing to challenge the person directly.

Okay so now we have four possibilities on our graph, but today I want to focus on the top area of the chart, the area where you care personally about the other person. If you don’t care about the person, then… well I could convince you about why you ought to care for your colleagues but I don’t have time for it right now. So let’s assume that you care.

Alright let’s take a look at the top right corner, where you care and you’re willing to challenge directly.

This area is where radical candour lives. It’s when you care enough about a person to ask difficult questions, to share difficult feelings, and to have difficult conversations. It can be an uncomfortable place at times.

Your instinct might be to avoid the difficulties of talking to someone about something uncomfortable. That would be the top left corner of our graph, where you care but you’re unwilling to challenge someone directly.

This area of the graph is called “ruinous empathy” because you care about someone but you’re unwilling to have difficult conversations. It really is ruinous: you think that by avoiding a difficult conversation you might be helping a person, but avoiding difficult conversations is only helping yourself.

(Side note: this is why I get so mad when people diminish non-technical skills as “soft” and imply they aren’t difficult – they are! These are all difficult conversations, but radical candour is a skill and habit you can get better at.)

Psychological Safety is a really useful idea that is unfortunately being co-opted and misused by managers and CEOs.

The technical definition of psychological safety is "a measure of the comfort of a team to take interpersonal risks”, but that doesn’t really mean anything unless you do a lot of reading.

Instead, I like to think of psychological safety as "the degree to which your team feels safe learning from its mistakes.” A psychologically safe environment is one where people feel safe asking questions, pointing out and admitting mistakes, and take risks without fear of being ridiculed by their teammates. Only a psychologically safe team is able to examine and learn from their mistakes, without needlessly judging themselves.

Every person makes mistakes, and every team makes mistakes. They happen, in every setting imaginable, even on high-stakes medical teams. Like suffering, we can try to avoid and minimize mistakes, but they are inevitable.

We must must must learn to accept our mistakes and to discuss them. Only then – when your team is comfortable with their own mistakes – will your team be able to learn from them.

When I was researching this presentation, I read through the Artsy blog archive. Not the Artsy Engineering blog, but the Life at Artsy blog. And I came across this article on open sourcing our company culture, which I collaborated on in 2015, predating my research into team dynamics.

Being open with your errors and identifying the insights gained can help others avoid the same blunders and keep your team on-track.

Now that I have the vocabulary to describe compassionate and toxic workplaces, it’s remarkable to me how well this quote characterizes psychological safety.

Psychological safe work environments are also places where asking questions is a normal and expected part of work. Try to foster an environment of curiosity and learning by asking questions, especially if you’re a senior developer. If you’re only 99% sure you know the answer to a question, then ask it anyway. 99% isn’t enough.

By asking questions, you are signalling to the rest of the team that asking questions is normal, and expected of them. This is especially important for teams with junior developers.

I tend to take ideas to their extremes, and fostering an environment focused on learning is an extreme that I embrace. More important than what your team builds is the learning process of building it. Say that your team is building an app. You’ve never built that app before, right? So instead of focusing on building the app, focus on learning how to build the app and the app itself will naturally follow. Because your teammates care more about learning than they do about being ridiculed for making a mistake or asking a question, you catch bugs faster. You identify bottlenecks sooner. You anticipate problems before they manifest themselves.

Remember: you’re not just learning, you’re learning as a team, so you benefit from everyone’s experience.

Regarding compassion, it is far, far better to extend compassion to someone who might take advantage of it than it is to withhold compassion from someone who might need it. Remember the prime directive: we’re all doing our best; start from that shared understanding and you can foster compassion.

Teams are the Sum of Teamwork

There’s a really useful term for discussing team work, but before we get there I need to tell you about Buckminster Fuller.

He was an American architect, systems theorist, author, designer, and inventor. President of Mensa. Smart person. And in the 60’s and 70’s, Buckminster Fuller spoke at universities around the world and used that opportunity to popularize a word. The word described an enormously useful idea, and he was aghast that it didn’t catch on.

Sadly, the word did eventually catch on with opportunistic CEOs and product managers. It became overused and through overuse, the word became devalued. Unfortunately, when we devalued the word, we seem to have devalued the idea, too. And that word is… synergy.

Synergy means behaviour of whole systems unpredicted by the behaviour of their parts taken separately.

He also said: "there is nothing in the chemistry of a toenail that predicts the existence of a human being.” If you need a more technical example:there’s nothing in the mechanics of DNS that predicts the existence of the world wide web.

Synergy is essentially a word for the idea that a whole is larger than the sum of its parts.

It’s such a shame that “synergy” has fallen into disuse because this is a very useful idea, and it’s difficult to have a conversation about ideas without actually having a name for them. So: let’s bring “synergy” back! Let’s reclaim it from the waste bin of history. I’m going to use the word “synergy” unironically and I encourage you too as well.

This is a photo from 2015, taken at Artsy’s first ever art auction we ran with Sotheby’s, one of the largest auction houses in the world. It was a huge deal – months of work had built up to this night. The future of the Artsy auctions business hinged on this event.

We were all there to ensure that the product we’d built together performed flawlessly. But there are only four engineers in this photo (one of them is the CTO). The rest are auction liaisons, marketers, support staff, project managers, and others.

If you think about how a typical software project is managed, it includes more than just programmers. Technology is the product, but the developers are only a part of that team. A programmer working by themselves would not produce a very compelling product.

It’s the responsibility of the team leaders to facilitate a team structure where the design team, the developer team, the support team, etc are appropriate aware of each other. Not everyone can be aware of what everyone else is doing; cross-team communication can easily become overwhelming, so it needs to be done with care and attention.

And indeed, this kind of synergy has business precedence.

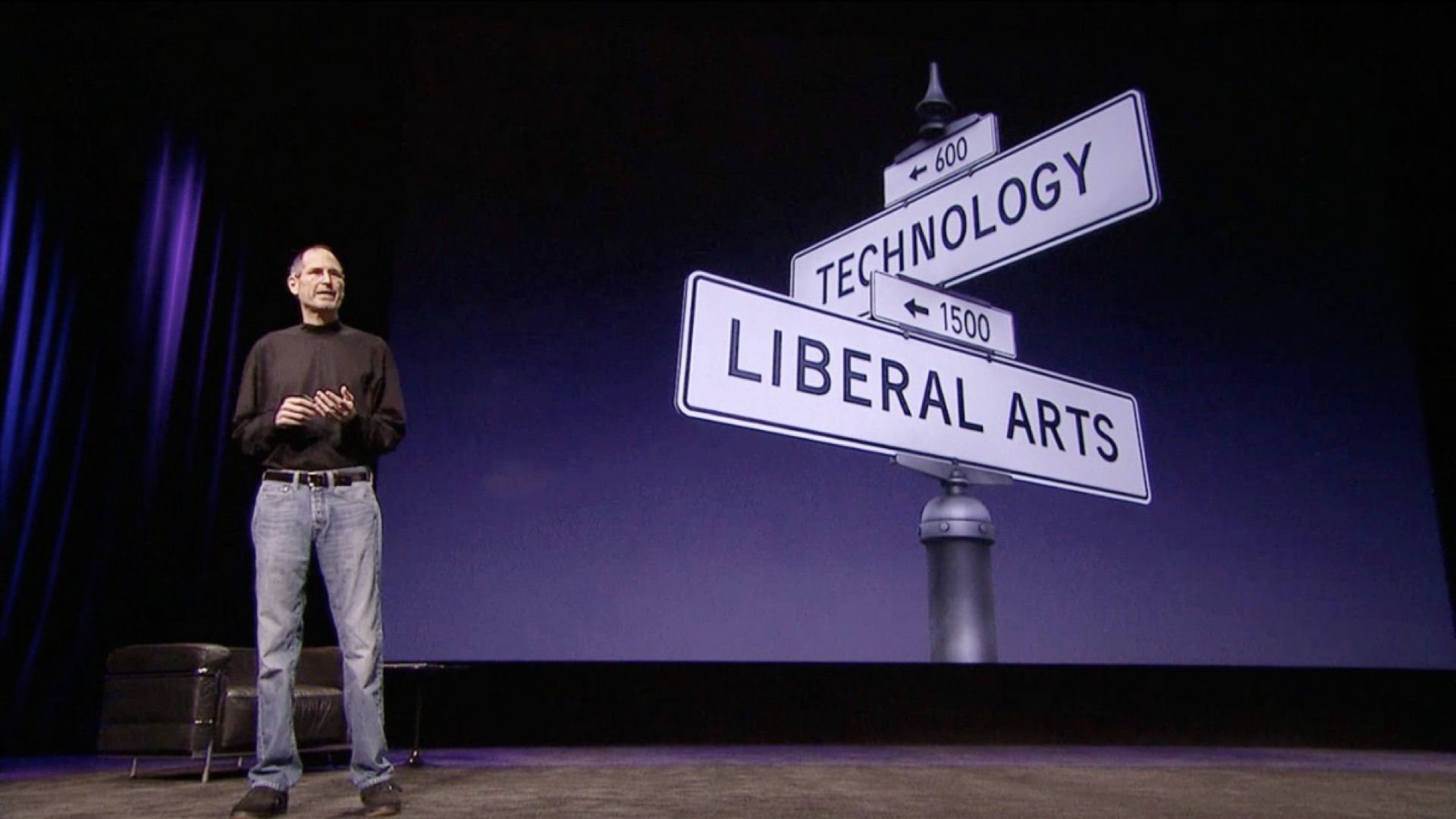

(Note: I generally don’t like quoting Steve Jobs in conference presentations because it’s kind of cheating: we all know who he is and we are all familiar with his work. Many of us admire him. But what he has to say applies really well here.)

I have many criticisms of how Steve Jobs managed teams, but he did get this right. He famously said:

It’s in Apple’s DNA that technology alone is not enough. It’s technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields the results that make our hearts sing.

Wake up, people! He’s describing synergy!

And he’s describing a business success that is only possible through cross-team collaboration, through knowledge-sharing. A diverse team of teams working towards a common, well-defined goal.

Synergy can exist in any team, but I believe that it is fostered best in teams that exhibit psychological safety.

So what can synergy look like?

At Artsy, I helped run a month-long, once-weekly course in Swift. We designed two tracks: one for people who could explain what “Object-Oriented Programming” means, and another for everyone else.

We took care to foster an environment where our non-technical colleagues could learn about coding and ask questions about how programming works. As a result, we fostered a broader work environment where they felt comfortable asking questions. We increased the psychological safety of our team, gave our colleagues the vocabulary to ask even more interesting questions, and we have been rewarded by a better team. A team that feels comfortable asking questions about products before they’re built, pointing out potential bugs before they get written, and contributing in ways we never anticipated.

(Side note: it took a lot of composure not to tear up during this part of my presentation because I’m so proud of the work we’ve done and the work of my non-technical colleagues who took the time to learn more about how software gets built.)

Remember that humans are naturally empathetic. Any parent can tell you that when babies hear another infant crying out, they start crying out too. These infants are only a few days old and don’t have language skills, but they sympathize with other reflexively. This sympathetic crying is hardwired into our brains from birth.

Humans are not Epicureans, driven solely by rational self-interest. I reject psychological egoism. Human beings are complex individuals driven not only by self-interest, but also driven by a fierce need to care for others. Humans are empathetic by nature and it is only when obstacles are erected in our path that we ignore this drive to care.

Society erects social barriers that prevent us from caring for others. These barriers often manifest themselves as judgements we make about others. “That person on the street asking me for money should just get a job” is a judgement, and it shuts down our ability to care for that person.

And so too do workplaces erect barriers to caring, and so too do they manifest as judgements. We judge each other (and ourselves) whenever we use the word “should”.

- iOS developers should use Swift instead of Objective-C.

- React Native developers should just learn a real language.

- Designers should just learn to code.

All of these judgements shut down our ability to empathize, to care, and to be compassionate. And we see violations of our prime directive: to assume that everyone is doing the best they can, given their circumstances.

One really common form of these barriers manifesting themselves on software team is what people call “brutal honesty.” There’s this idea that as long as what you’re saying is true, it doesn’t matter how you say it. In fact, how you say something matters just as much as what you’re saying.

Compassionate honesty. What an amazing idea! A form of honesty that tries to minimize suffering. Radical candour doesn’t mean you have to hurt someone’s feelings to tell them a truth – radical candour is only radical because you care, so make sure that your honesty conveys that sense of caring for others. Synergy is when a group behaves in a way not predicted by the behaviour of its constituent components. We foster synergy in software teams by being compassionate, by caring for each other, by staying non-judgemental.

In the absence of obstacles, humans will care.

We foster synergy through psychological safety, and we recognize that humans will care for one another by default if unimpeded by their environment.

Conclusion

We talked about a lot today. Starting with the connection between team quality and team outcomes, we discussed compassion in the workplace: what it looks like and how to foster it. And we concluded with a discussion of synergy. (I hope you all start using that word!)

I have spent the past two and half years learning about this stuff, and I’m definitely not done. But I’d like to offer a jump-start on your own journeys: I have some recommended reading for you. This is not an exhaustive list, of course, but these are resources that I have found useful in my own path to learning about compassion at work.

The first is a book, Awakening Compassion at Work, an excellent book that puts the business case forward for compassion.

Compassionate Coding, a firm run by April Wensel, which helps companies build compassionate teams. Check out their blog for sure!

Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth is a book by Buckminster Fuller. It is a collection of steps that humanity needs to take if we are to survive the 21st century. It profoundly changed the way I think about systems generally, including teams.

Inclusion is a Captain’s Job by Danilo Campos is a conference talk-turn-blog post about lessons of inclusion from the Star Trek canon. The good Star Trek canon. And he 100% presented the talk in a Starfleet Engineering uniform:

Now that we’re at the end of this post, I have something really important to tell you…

You will never finish.

You will never finish working towards compassion. Your education in compassion, your pursuit of building better teams, will last the rest of your life.

It is critical to remember this. Us engineers are used to thinking about tasks in terms of GitHub issues to be closed or Trello cards to move to the “Done” column, but building compassionate teams is not something you can ever call “finished.”

You must accept the fact that your work will never ever be complete, and you must commit yourself to the pursuit of the shared compassion of humanity.